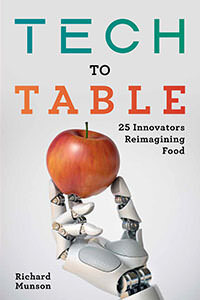

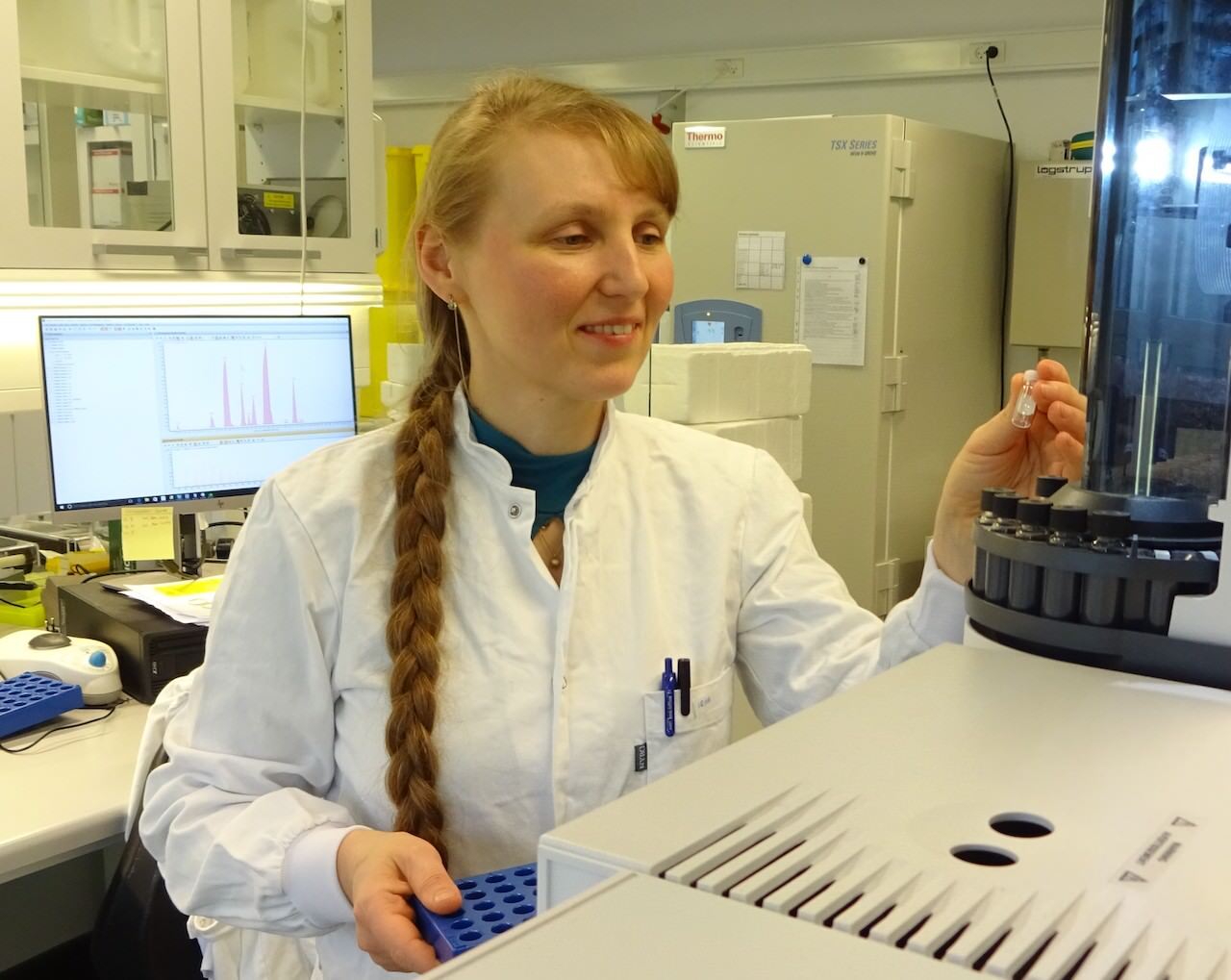

Irina Borodina, BioPhero — Curtailing Farm Poisons by Messing with Pest Sex

Conventional insecticides kill virtually every insect in a field, including pollinating bees and natural predators of crop pests. Such poisons harm farmers and birds, degrade biodiversity, and leave unhealthy residues on fruits and vegetables. A growing number of pests, moreover, develop resistance to synthetic pesticides, forcing farmers to deploy more and more toxic chemicals.

Irina Borodina offers an alternative. The approach—pheromone-based pest control—has been around for a few decades, but the founder of BioPhero has devised ways to make pheromones more cheaply and to protect a variety of crops.

The process involves sex—actually the blocking of copulation by cotton boll worms, diamondback moths, rice stem borers, fall armyworm, and other crop-destroying pests. Bordeaux winemakers first used such pest control in the early 1970s and, appropriately, called it La confusion sexuelle.

Confronted by the ravenous larvae of the moth genus Cochylis, the vineyard owners decided to try a bit of erotic trickery. They knew that female moths emit an airborne plume that contains a specific chemical blend designed to attract a mate of the same species. Horny males detect that pheromone at minimal concentrations of a few hundred molecules in a cubic centimeter of air, and then track the scent for thirty miles to locate the “calling” female. After being impregnated, the mother lays lots and lots of eggs that develop into those larvae devouring Bordeaux vines. To avoid such destruction, the vineyard owners decided to deceive the male.

Called “mating disruption” in English, the winemakers released a synthetic pheromone that closely mimicked—and, therefore, masked—the female insect’s plume. Confused males could neither find nor impregnate females, which, to the delight of the winemakers, cut the rate of successful mating and collapsed the insect infestation.

Other farmers subsequently directed such mating disruption at pests damaging apples, pears, and other high-value crops. The process proved effective and provided numerous complementary benefits. Since the covert pheromones, for instance, confuse only the males of the targeted species, beneficial insects, pollinators, and birds remain safe. Since pheromones contain no toxins, evaporate over time, and do not persist in the field or on crops, the United States Environmental Protection Agency judges them to be among the most environmentally friendly means to exterminate pest invasions. Compared to conventional and toxic insecticides, pheromones do not harm farmworkers, and insects, finally, do not develop resistance to mating disruptors.

Yet this old-style form of mating disruption has suffered limitations. First, the traditional processes to develop and produce pheromone copies rely on expensive and specialized chemicals as starting materials. As a result of their high costs, sex-inhibiting pheromones have been limited to 0.1 percent of the world’s fields that grow fragile produce (approximately one million acres) and have not been deployed on corn, soybeans, rice, and other row crops that represent more than a third of the global farmlands (about 100 million acres). Growers, moreover, have had to release the deceptive plumes by hand, which is time consuming and costly. Third, because conventional mating disruption targets a single destructive insect, farm fields with multiple pests have required a more complex approach, often referred to as “integrated pest management,” that includes various pheromones, soil management, and crop rotations.

Borodina wants to eliminate those limitations. “It’s all about metabolic engineering,” she declares. The entrepreneur developed a biotechnology-based alternative to conventional pheromone production. In a scientific paper, she explains, “This required reconstruction of synthetic biochemical pathways towards pheromones in yeast, extensive engineering of the yeast host to improve the flux towards the products, and optimization of the fermentation processes.”

Borodina’s process, which she claims will transform pest management, begins with identifying the specialized enzymes that insects naturally use to create pheromones. She then expresses an identical pheromone into yeast, which comes from a family of cells widely used in food production. This engineered yeast ferments in large tanks, similar to those used to brew beer, but the output is more pheromones rather than ethanol. “This biotechnological process,” she says, “is the same as the one used to produce enzymes for food and washing powder, and insulin for diabetes.” For farmers and consumers concerned about sustainability, her yeast feedstocks are renewable and the pheromones are biodegradable.

Borodina first concentrated on moths, particularly the corn borer whose larvae destroy grain crops. She then turned her attentions to the cotton bollworm attacking Brazilian soy fields and the fall armyworm devastating corn crops in Africa.

Borodina wants natural pest disruptors to be used widely and works with other firms to improve distribution—and application. Growers or their contractors in the past placed by hand throughout the fields polymer capsules that control the release of droplets of pheromone; another approach traps insects to glue boards containing pheromone bait. In contrast, farmers can spread BioPhero’s cheaper product far and wide with crop dusters or tractor-towed sprayers, both common machines producers already utilize.

The agricultural pheromones market was valued at $1.9 billion in 2017, but some business analysts expect it to grow almost 16 percent annually to $6.2 billion by 2025. In contrast, yearly sales of chemical insecticides surpass $17 billion, suggesting to Borondina that alternative approaches have the potential to expand even more substantially.

Borondina claims her product is already less expensive than spraying synthetic chemicals and can be used at a large scale on row-crops. Part of that advantage comes from having to apply pheromones only once a year, during the flight phase of the insect, whereas insecticides generally must be sprayed several times a year. She also argues that new advances in biotechnology will further reduce BioPhero’s production costs.

Borondina sees pressure for change coming from consumers who are becoming warry of pesticides, as well as from the pesticide industry whose high development costs limit the pipeline of new synthetic insect killers. Worried about health and environmental damage, regulators increasingly restrict the chemical-insecticide options available to growers, yet the broken regulatory system also makes it hard to obtain approvals for environmentally beneficial pesticides, thus extending the shelf life of more harmful chemicals. Farmers want safer biological alternatives, says BioPhero: “The future of pest control is not killing insects. It’s disrupting their mating patterns.”